Why Social Engineering Works: The Psychology of Cybercriminal Tactics

Table of contents

You can patch systems and strengthen firewalls, but the hardest thing to secure is the human mind. Cybercriminals understand this better than anyone. However advanced their tools become, every attack still depends on a moment of trust, fear, or misplaced confidence.

Modern attacks are as psychological as they are technical. Hackers rely on persuasion more than code. They pressure people to act quickly or speak carelessly. Let’s explore how that manipulation works, through the story of a BBC journalist who was targeted, the Medusa ransomware group’s methods, and the personal toll on defenders after major breaches.

1. Social engineering: What it is, and how it works

Social engineering is the art of psychological manipulation, where cybercriminals trick individuals into divulging confidential information or performing actions that compromise security.

Unlike direct hacking, which targets system weaknesses, social engineering targets cognitive biases, emotional responses, and etablished patterns of social interaction.

Social engineering tactics work because humans are the most susceptible attack vector. Consider these alarming figures:

- 95% of data breaches involve some form of human error

- 42% of organizations reported phishing and social engineering attacks in 2024

- 54% of people can’t identify an AI-generated phishing email

Ultimately, people are the biggest threat to your attack surface. Let’s explore the social engineering tactics that can be used to manipulate them, before exploring a real-life case study to see them in action.

The 6 main social engineering tactics

Social engineering techniques work by understanding how people think. These methods echo classic persuasion principles, applied under pressure.

- Authority: Pretending to be a manager, IT admin, or law enforcement. People obey instructions from perceived power.

- Urgency: Creating fake deadlines to force quick reactions.

- Familiarity: Posing as someone the target already knows.

- Scarcity: Claiming that time or access is running out.

- Reciprocity: Offering help first, to create a sense of obligation.

- Social proof: Suggesting that others have already complied.

Each tactic plays on instinct, not logic. Most victims act on impulse, after receiving some kind of psychological pressure. There isn’t time to reflect or reason; their natural reflexes take over, and can lead to devastating consequences.

Top 12 social engineering attack mediums

We’ve talked about the vulnerabilities that social engineering can play upon. Now, let’s explore the types of campaigns it can feature in.

- Phishing attacks: Fraudulent emails that mimic trusted senders.

- Spear phishing: Targeted phishing that uses personal details.

- Whaling: Attacks aimed at executives, where the stakes are financial or reputational.

- Smishing: Text message scams that trade on immediacy and convenience.

- Vishing: Voice calls that impersonate help desk, vendors, or regulators.

- Scams and impersonation: Fake offers, bogus invoices, or false job approaches to lure a response.

- Malicious code and trojans: Attachments or downloads that drop malware. Social engineering gets the user to run the file. The code does the rest.

- Automation and credential stuffing: Attackers reuse leaked passwords at scale.

- VPN and remote access abuse: Requests to whitelist an IP or install a remote tool are framed as urgent fixes. Once installed, attackers move laterally.

- Denial of service and DDoS: Overload a service to create chaos. Teams rush to respond, and that chaos can mask other intrusions and drive risky shortcuts.

- Downtime and operational disruption: Attacks that create outages force emergency decisions, and these rushed actions increase the chance of human error.

2. Case study: Mind games on a BBC journalist

When BBC reporter Joe Tidy received a message promising him wealth, it began as a conversation on the encrypted chat app Signal. The person claimed to be part of a cybercriminal group called Medusa (more on this group later), specializing in ransomware attacks.

“You’ll never need to work again,” they said, if he helped them gain access to the BBC.

Joe had no intention of complying with the cybercriminals’ demands. But he was curious to understand the psychological pressure tactics behind cyberattacks. So he continued the conversation and documented the whole process in a BBC article.

What unfolded was a study in pressure and persuasion.

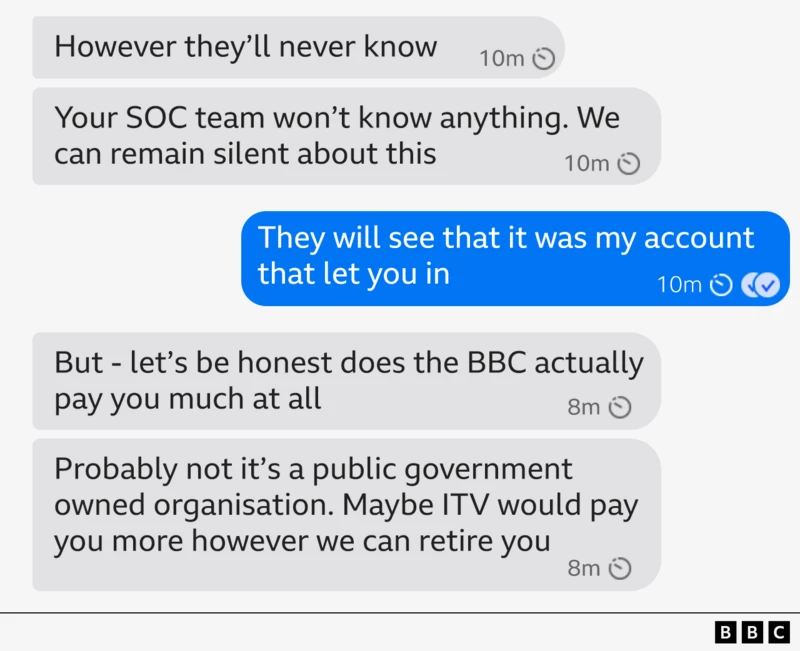

- Initial contact: A stranger called ‘Syndicate’ contacted Joe on a secure messaging app, although they changed their name to ‘Syn’ mid-conversation.

- Offer: The criminal offered a large financial reward if Joe helped to compromise the BBC’s systems. They said, “If you are interested, we can offer you 15% of any ransom payment if you give us access to your PC.”

- Manipulation: They built rapport slowly, alternating between encouragement and subtle pressure. They even suggested a $55,000 deposit, as an act of goodwill. If ignored, they sent follow-up messages and increased the frequency of contact.

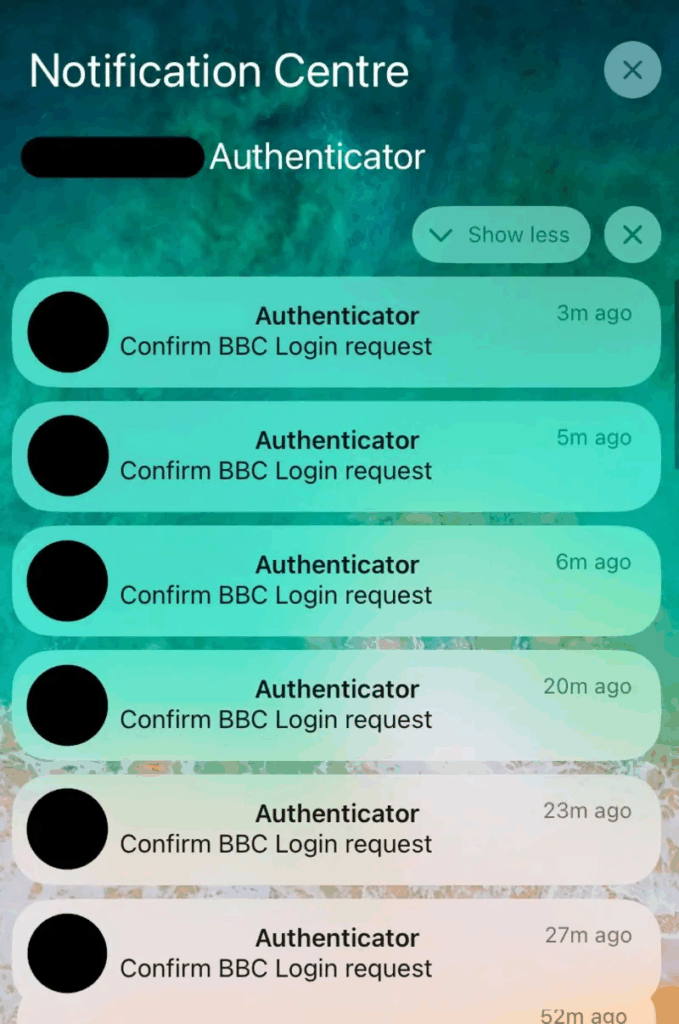

- Psychological escalation: The hackers began using MFA bombing tactics to cause stress and confusion. They repeatedly triggered multi-factor authentication requests to the journalist’s accounts, before then sending a polite apology: “We were testing your BBC login page and are extremely sorry if this caused you any issues.”

- Ramping up pressure: As Joe resisted, the tone shifted from charm to irritation. Messages became more insistent: “I guess you don’t want to live on a beach in the Bahamas?”

Joe kept in sync with the BBC information security team throughout the conversation, and as a precaution, he temporarily disconnected from the BBC network entirely. But after a few days, the malicious actors deleted their account and vanished.

The BBC was not compromised by this incident. But it provided an insightful perspective into how threat actors pressure their potential victims, and nurture potential insider threats who might even willingly contribute to a breach.

The group behind the pressure: Medusa

Joe Tidy’s contact claimed to come from Medusa, a ransomware group that specializes in psychological pressure.

While originally a single cybercrime group, Medusa now operates with a Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) model. This means anyone can pay to use their malicious software to steal sensitive data, then threaten to publish it unless a ransom is paid.

To date, it’s targeted over 300 victims in critical infrastructure, including healthcare, technology, and manufacturing.

Common Medusa tactics include:

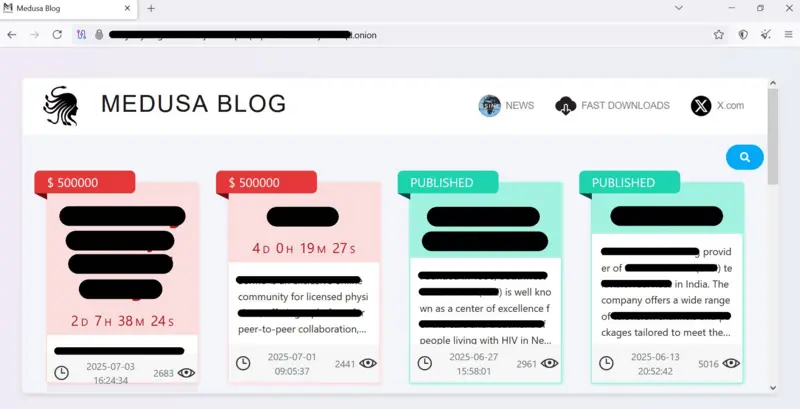

- Naming victims on leak sites with visible countdown timers (see below)

- Sending mixed messages that are polite one moment, and mocking the next

- Offering false reassurance to lower resistance, such as in Joe Tidy’s case

- Using phishing campaigns (e.g. malicious links or attachments) that lead to infostealers

Medusa follows every rule in the social engineering playbook, keeping people under constant pressure until their rational thinking disappears.

Each move is designed to destabilize. Victims are forced to make decisions in fear and confusion, which leads to costly mistakes.

3. Bonus story: When the hackers just ask

In a different social engineering case, the attackers didn’t even need malware. They just used confidence and a calm voice.

Here’s the timeline of the 2023 Clorox hack:

- Impersonation: The hackers, affiliated with the Scattered Spider group, called Cognizant’s IT help desk, pretending to be Clorox employees who’d lost access.

- The request: They claimed they couldn’t log in and asked for credentials to be reset.

- The slip: The support agent complied without verifying who was on the line.

- The transcript: “I don’t have a password, so I can’t connect.”“Oh, OK. Let me provide the password to you, OK?”

- The result: Attackers gained entry, causing an estimated $380 million in damages.

This vishing attack worked because it felt routine. A polite voice on the phone is harder to question than an email with a suspicious link. And it goes to show that sometimes, malware isn’t even needed. A convincing story (and a cooperative help desk) can open doors all on its own.

Figure 5: Headline featuring the story. (Source: NBC News)

4. The human cost of a single mistake

Financial losses and disrupted business operations are an inevitable consequence of cyberattacks. But people rarely discuss the psychological shockwaves that reverberate within teams, long after the initial breach.

Tim Brown, the Chief Information Security Officer at SolarWinds, learned this firsthand after the 2020 Russian-led supply chain attack. In the days that followed, he barely slept. He lost 25 pounds in 20 days, suffered a heart attack, and described feeling like he was “running on adrenaline,” in an interview with The Guardian.

The stress didn’t stop once the breach was contained. Investigations, lawsuits, and public scrutiny kept the pressure alive. Brown now advocates for mental health support in cybersecurity, urging teams to treat emotional resilience as part of incident response plans.

The mental fallout from a cyberattack can last for months, or even years. When targeted attacks happen, the human toll often hits hardest behind the scenes, especially among the people trying to fix them.

5. Checklist: How to secure the human firewall

Even the strongest cyber defense can falter if people aren’t prepared. Here are some security measures that every team should follow.

- Strengthen awareness with real threat intelligence: Training should go beyond generic phishing examples. Share current intelligence on social engineering tactics, recent scams on social media, and examples drawn from your own sector. When people see what real-world potential attacks look like, they learn to spot suspicious activity faster.

- Establish layered access controls: Limit what any one employee can reach inside computer systems. This simple step helps prevent unauthorized access and stops insider threats from spreading. Role-based permissions and multifactor authentication should be standard across operating systems and endpoints.

- Combine policy with psychology: Most breaches succeed because employees stay silent after realizing they clicked a link or shared personal data. Clear reporting lines and rapid, real-time support help mitigate damage before it spreads through the network.

- Protect intellectual property and personal data: Intellectual property, design files, or financial records have long-term value on the dark web. Encourage teams to label and encrypt sensitive information, store regular backups, and confirm where data is shared externally.

- Keep antivirus and endpoint protection up to date: Automation allows threat actors to strike within minutes. Continuous updates, managed patching, and regular security audits reduce that window. Antivirus tools alone are not enough, but they remain a vital baseline for mitigating potential threats and detecting malicious code early.

- Integrate human behavior into cyber defense planning: Incident response plans should include the psychological dimension: stress, fatigue, and confusion. Create clear playbooks so no one has to improvise during an attack.

- Learn continuously from audits and near misses: Every phishing email that reaches an inbox, every failed login, and every false alarm adds insight. Treat those moments as intelligence. Regular internal audits, combined with external threat intelligence tools such as CybelAngel, help organizations refine both processes and people.

Building a reliable “human firewall” means giving employees the structure to make good choices under pressure. That means that when they’re targeted, they’ll have the right gut reaction.

Conclusion

Social engineering remains one of the most enduring cyber threats because it targets people, not technology. Every attack is designed to exploit instinct before reason.

CybelAngel delivers real-time external threat intelligence across the open, deep, and dark web, helping security teams detect leaks, stolen credentials, and other early signs of social engineering campaigns before they reach employees.