What is a Web Shell? Here’s Everything You Need to Know

Table of contents

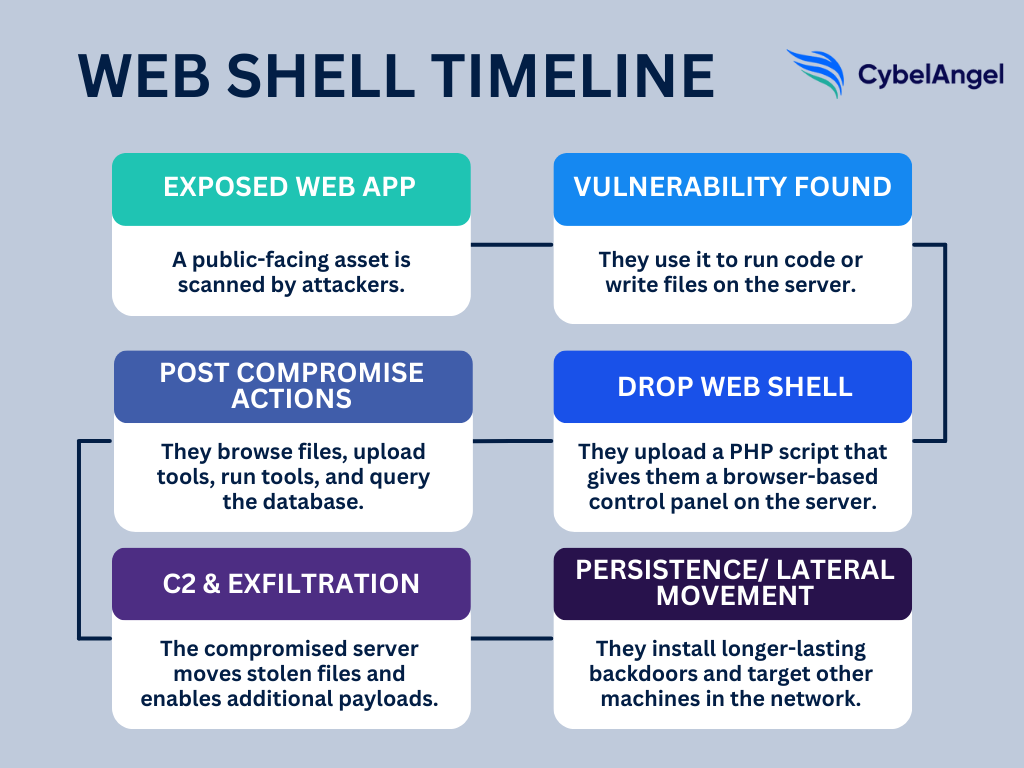

Threat groups deployed web shells in 35% of incidents during Q4 2024. That’s more than triple the rate of the previous quarter. Once it’s on a compromised web server, a web shell gives attackers long-term persistence, the ability to move laterally, and direct access to sensitive data.

Let’s dissect a classic PHP web shell to show how it works in practice. By breaking down features like file browsing, command execution, and database access, you’ll see why these scripts are so effective at turning small vulnerabilities into lasting cyberattacks.

Why web shells matter

A web shell is a small script (usually written in PHP, ASP, or JSP) that attackers upload to a vulnerable web application.

Think of a web shell as a hidden control panel. Once installed, it lets hackers run commands, browse files, and take over the server from their browser. What starts as a single flaw in a web app can quickly become a permanent backdoor.

According to CISA, web shells can operate on Linux, Microsoft Windows, macOS, and Network platforms.

Attackers usually plant web shell scripts through:

- Remote code execution bugs in public web apps

- Poorly secured file upload forms

- Remote or local file inclusion (RFI/LFI) flaws

- Outdated CMS plugins or themes, such as in WordPress

Over the years, some shells have become infamous:

- C99 web shell: A feature-packed PHP shell with tools for file management, command execution, and databases

- China Chopper webshell: A tiny but powerful web shell often used for stealthy persistence

- R57 and WSO web shells: Older but still active web shells with basic file and command features

- B374K web shell: A PHP web shell that can view processes and run commands

Let’s look at some of these web shells in action.

Case studies: Real-life web shell incidents

Before we break down their components, let’s look at some real-life examples of the damage web shells can do. They accounted for 35% of cyberattack incidents in Q4 2024, making them a major malicious script to watch out for.

- April 2025: According to The Hacker News, critical bug let attackers upload JSP web shells, then use tools like Brute Ratel to escalate and steal data. Scans found hundreds of vulnerable servers exposed online.

- July 2023: CISA reported that threat actors exploited the Citrix NetScaler/ADC flaw (CVE-2023-3519) to drop web shells (often JSP), gain remote command execution and persistence, and move laterally.

- June 2022: MITRE ATT&CK documented how a web shell was deployed during the Ukraine Electric Power Attack, executed by a threat group with Russian connections.

In short, web shells can quickly turn any vulnerable app into a compromised web server, with devastating consequences.

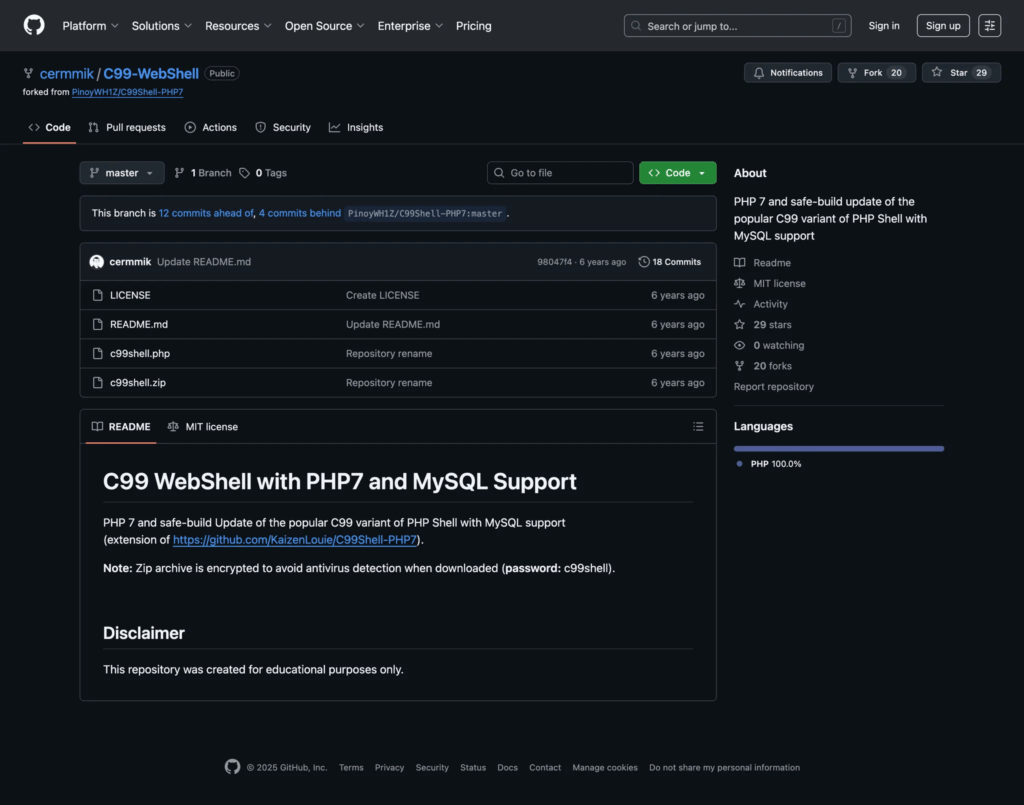

C99: A webshell analysis

C99 is a classic PHP webshell example that packs a lot of capability into a single script, including:

- File manager

- Upload/ download

- Command execution

- Database helpers

- Self-delete option

C99 clearly demonstrates the full attacker workflow: an adversary drops a tiny PHP file through a vulnerable upload or RCE, then uses that same script to browse the webroot, run OS commands, pull credentials and stage further tools.

Let’s break down what the C99 webshell can look like in more detail.

Figure 2: C99 webshell code information in GitHub. (Source: GitHub)

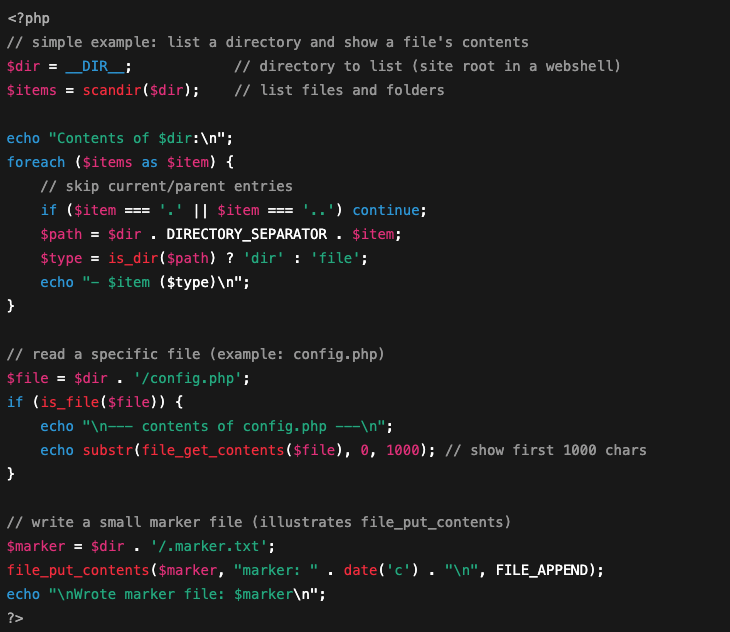

1. File system navigation

- What it does: file-system navigation lets an attacker list folders, open files, and read their contents. They might use functions like

scandir()oropendir()to see what’s on the server,file_get_contents()to read files, andfile_put_contents()to drop or update files. - Why it matters: This is how hackers can find config files, API keys, backups and other sensitive data, and where they stage additional payloads.

- What to watch for: Requests repeatedly hitting the same PHP path that return directory listings. Also check for new or recently-modified files in webroot (odd timestamps), and sudden reads of config files or large downloads initiated from the web server.

The snippet below is a simplified example to show the behaviour, although exact implementations and function names vary by variant.

Figure 3: Example of file system navigation in PHP programming language.

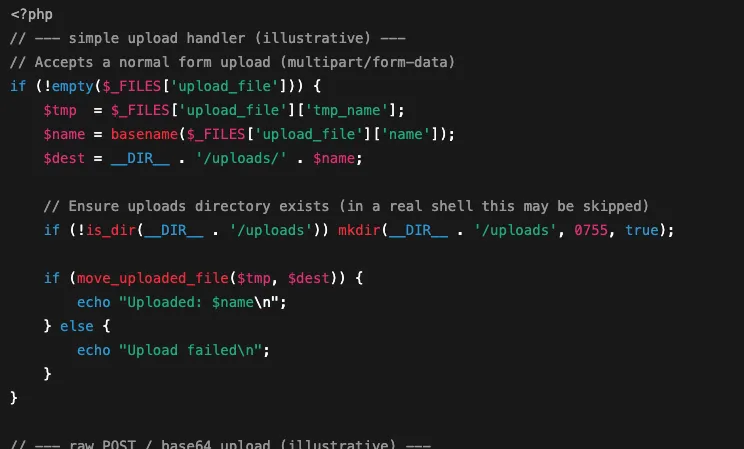

2. File upload/ download

- What it does: C99-style shells often include a file upload form so an attacker can drop extra tools (malware, scanners, or large payloads) onto the server. They also let attackers download files from the server. Common upload mechanisms are

move_uploaded_file()(standard browser file uploads), handlers that accept raw POST bodies, or POST fields carrying base64-encoded files. - Why it matters: An attacker uses uploads to stage further malware or replace app files. Downloads let them pull configuration files or database dumps out of your environment, all through the webserver process.

- What to watch for: Keep an eye out for large or unusual POST requests to the same PHP endpoint (especially those containing long base64 strings) followed by new or oddly named files appearing in web-accessible folders or spikes in outbound traffic.

3. Command execution/ Remote access

- What it does: C99 gives an attacker a tiny web terminal. They can send a command via the web UI or a POST request and get the command output back in the browser.

- Why it matters: This is how attackers spawn reverse shells, run privilege-escalation scripts, or launch other tools from the web server.

- What to watch for: Monitor for web processes spawning shell commands or unexpected outbound connections immediately after requests to a single PHP endpoint.

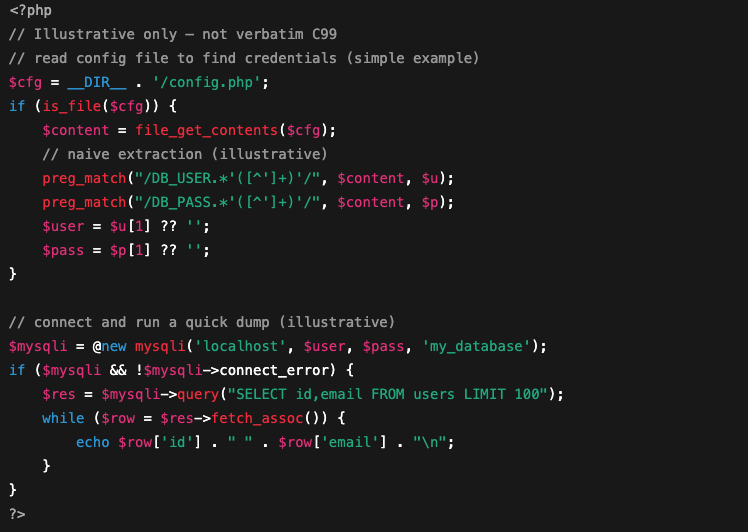

4. Database connections and data extraction

- What it does: C99-style shells often include quick tools to read config files (where apps store DB credentials) and run SQL queries using those credentials. That lets an attacker dump user tables, steal API keys, or write new records to help persistence.

- Why it matters: With DB access an attacker can exfiltrate customer data, take over accounts, or use the same credentials to access other services, multiplying the breach impact.

- What to watch for: Look out for unexpected reads of config files plus unusual DB connections/queries originating from the web server process.

5. Obfuscation and anti-forensics

C99 variants sometimes hide strings or logic using base64_decode(), gzinflate() or eval() wrappers, and may compress or split payloads to avoid simple signature detection. They may also self-delete after use. These tricks make signature-based scanners and quick manual reviews miss the implant.

How attackers deliver web shells

Now we’ve seen the inner workings of a web shell operating system, let’s explore how hackers get them into a compromised system in the first place.

- Exploited remote code execution (RCE) in a public app: Attacker runs code on your server

- Unsafe file-upload endpoints or misconfigured permissions that let attackers drop files

- Remote File Inclusion (RFI) or Local File Inclusion (LFI) chains that let an attacker force the server to write or execute a remote file

- Compromised plugins or themes, stolen admin credentials, or phishing that gives access to admin panels (common in WordPress)

Checklist: How to catch a web shell

Here’s a clear checklist you can use during hunts or triage. Each item is one place to look, and what it usually means.

- New or oddly named PHP files in web folders: Check for files that weren’t there before, have strange names (random strings), or timestamps that don’t match your last deploy.

- Unexpected outbound connections from the web server: Repeated, periodic connections to unknown IPs can be a beacon to command-and-control.

- Webserver spawning new processes or running shell commands: If your web process suddenly forks

sh,bash, or other unexpected binaries, treat it as high priority. - Changes to CMS core files, plugins, or unknown admin accounts: Look for modified core files, new admin users, or plugin files that don’t match vendor hashes.

- Odd POST requests with long bodies or base64-like data: Large or frequent POSTs to the same PHP endpoint (especially with long encoded strings) often indicate uploads or remote writes.

You can also benefit from monitoring tools.

For example, you can use file-integrity monitoring to spot new or changed webroot files, web application firewall (WAF) and web-server logs for weird POSTs, EDR alerts when the web process spawns shells or writes binaries, and network/ IDS for beaconing or unexpected egress. Combine those feeds and you’ll spot implants faster.

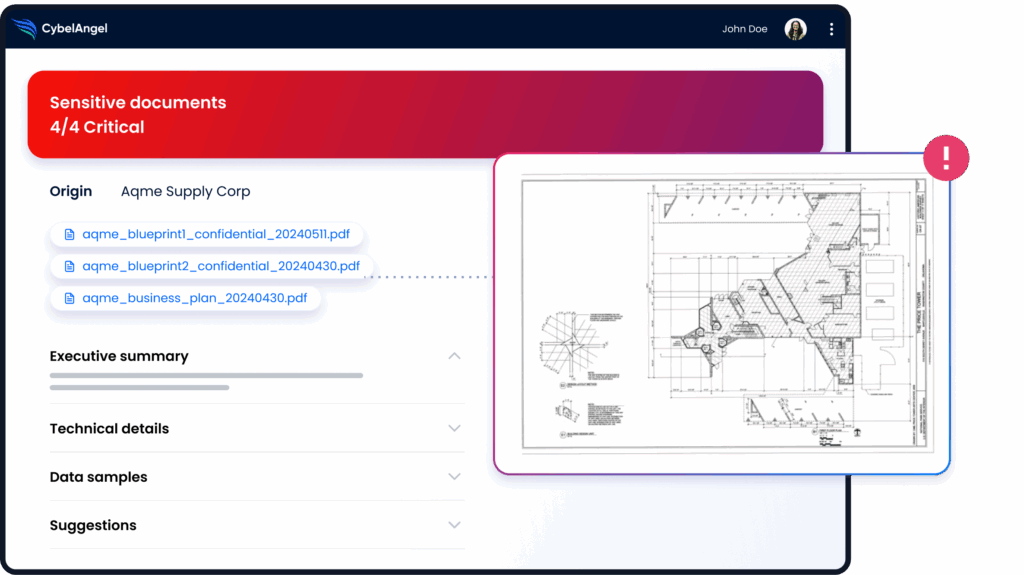

CybelAngel can complement this process. It can manage your public and internet-facing assets (which often hold the most sensitive data) and flag any issues before they turn into a full-blown breach.

7 tactical cybersecurity measures for CISOs

Here are some fixes that CISOs should prioritize to stay ahead of web shells.

- Patch public-facing apps and plugins: Apply vendor fixes quickly and automate updates where safe.

- Harden upload endpoints: Validate file types, strip metadata, reject executables, and store uploads outside the webroot.

- Tune your WAF for suspicious POSTs: Block or challenge large/encoded POST bodies and known web-shell signatures.

- Run file-integrity checks on the webroot: Hash content regularly and alert on new or modified PHP files.

- Lock down egress from web servers: Allowlist outbound destinations and block unexpected outbound ports.

- Improve credential hygiene: Rotate secrets, enforce MFA on admin panels, and alert on new/ privileged accounts.

- Use external threat intelligence to prioritise remediation: Map exposed apps, focus fixes on high-risk assets first, with tools like CybelAngel to automate the process.

FAQs

What is a webshell and how does it work?

A web shell is a small script an attacker drops on a website. Once it’s there you can control the server from a browser (run commands, read files, upload tools or pull data) all over normal web requests.

What are the common features of a webshell?

- File browser (list and read files).

- Upload/ download capability

- Run system commands (a tiny web terminal)

- Simple SQL/ query tools for databases

- A web UI or password-protected backdoor

- Obfuscation or self-delete options to hide traces

How do attackers upload a webshell?

They use weaknesses like a remote-code bug, an insecure file-upload form, an RFI/LFI chain, or a compromised plugin/ credential. Often a scanner finds the hole, and then an operator then uploads the shell and tests access.

What are the signs of a webshell on a server?

- New or oddly named PHP files in web folders

- Long or unusual POSTs (large bodies or base64 data)

- Repeated outbound connections from the web server (beaconing/C2)

- Webserver spawning unexpected processes or shell commands

- Modified CMS core files or unknown admin accounts

How can you prevent webshell attacks?

Patch web apps and plugins, lock down file uploads and store them outside the webroot, tune your WAF, run file-integrity checks and egress controls, and enforce strong credential hygiene (MFA, rotate secrets). Use external-asset mapping tools like CybelAngel to prioritise the exposed apps that matter most.

Why are webshells so dangerous?

They give attackers long-term access without needing new exploits. From one small script they can steal data, install more malware, and move through your network. And they’re often hard to spot until real damage is done.

Conclusion

Web shells can turn a single vulnerable web app into a full network compromise. They’re small and flexible, but the damage they cause can be catastrophic.

If you need help mapping and prioritising exposed assets and post-compromise signals, CybelAngel can automate discovery and surface the highest-risk places to remediate.