Banking System: A Rich Target for Cybercriminals

Table of contents

The infamous bank robber, Willie Sutton was once asked why he robbed banks. He responded, “Because that’s where the money is.” Nearly a hundred years later, the scenario has not changed, except bank theft has shifted from the physical world to the digital one. A few decades ago criminals robbed banks, now they’re hacking into them. Cyber criminals do not break into safes, they target customers’ credit cards. In 2019, a total of over 23 million credit cards were stolen or up for sale on dark web forums with the US and UK institutions being the main targets. Given the substantially developed financial ecosystems in these countries, it is the opportunity for huge financial gains driving this trend. In this article, we will examine these 2.0 criminals targets, and why banks and financial institutions should be worried.

Bank Vulnerability: 3 credit card theft use cases

Use Case #1: Identity theft

Identity theft is a multi-layered issue. It ranges from the simple access and use of Personal Identification Information (PII) to more problematic issues such as impersonation. This use case involves the interception of mail, direct physical theft, or pickpocketing. After pilfering the PII, the malicious actor impersonates the card holder and makes transactions in their name. In some cases, actors can take the deception a step farther by applying for a credit card using a victim’s identity. This is most easily accomplished in banking institutions that lack strict identification policies and procedures. You may be wondering why a bank would be concerned about these issues. The answer is simple: whenever there is a proven case of scamming, the bank handles both the burden of addressing the fraud and reimbursing the consumer.

Use Case #2: Physical skimming

Skimming a credit card is not as difficult as one might imagine. Despite the multitude of credit card readers, hackers and malicious actors have found vulnerabilities for nearly every payment system. Thieves can deploy highly sophisticated or extremely simply skimming techniques.  Source: anonymous post from a popular Dark web forum In less sophisticated instances, vendors, waiters, or cashiers simply snap a photo of credit cards for future use or to sell. In more complex schemes, skimmers (devices that read the magnetic strip on your card and store the card number or devices that can wirelessly intercept the card’s data) are purchased on the dark web or even over the public internet. These schemes force banks to create more secure payment validation systems (e.g.: 3D security, geotagging of transactions) and to limit the amounts of individual transactions. This is one of the reasons why some contactless payments are capped in European banks.

Source: anonymous post from a popular Dark web forum In less sophisticated instances, vendors, waiters, or cashiers simply snap a photo of credit cards for future use or to sell. In more complex schemes, skimmers (devices that read the magnetic strip on your card and store the card number or devices that can wirelessly intercept the card’s data) are purchased on the dark web or even over the public internet. These schemes force banks to create more secure payment validation systems (e.g.: 3D security, geotagging of transactions) and to limit the amounts of individual transactions. This is one of the reasons why some contactless payments are capped in European banks.

Use Case #3: Remote theft of financial information

Lastly, remote data theft can be summarized in the exposure of payment information during data breaches. This happens when hackers gain access to a business’ databases to siphon financial information directly or to gather enough private information (PII: name, identification, social security number, email, etc.) to carry out elaborate schemes to gain unauthorized access to credit card numbers through social engineering, phishing scams, malware attacks, etc. Alternatively, a hacker can gain remote access to personal servers and siphon unprotected financial information. This makes it difficult for the bank to trace the source of the scam — despite being liable to reimburse the client for the stolen funds.

Stopping the heist, a slow process

Credit card information is one of the most often shared pieces of data on malicious platforms. The volumes can be so high that it makes it difficult to track by issuers. Credit card issuers have meticulous monitoring processes, but these are most effective after a “suspicious” transaction is being made. Issuers rely on behavioral patterns and demographics, such as geographical location, time, IP, website, etc. to flag suspicious activity; however when malicious actors retain credit card data for extended periods of time, these behavioral and demographic triggers can be less useful. In summary, when a credit card information is stolen it is often too late to protect the victim and the issuing bank. While some banks are obliged to refund their customers in certain situations, this does not stop the aggravation of a stolen credit card. Banks continue to face an onslaught of credit card fraud, despite the plummeting sale price of a stolen credit card on the blackmarket caused by the never-ending supply of credit cards.

Credit card anatomy

Before we talk about how CybelAngel fights credit card fraud, it is critical to understand the anatomy of a credit card number. Every credit card on the planet has 12 to 19 figures printed on it. This string of numbers would make it difficult to trace cards back to their issuing authorities were it not for Bank Identification Numbers (BIN). BIN numbers have a specific sequence, which is essential for banking services. The first 6 (sometimes 8) numbers of a credit card are the bank identification numbers, and the remaining numbers are specific to the account. For example, Visa cards start with the number 4, while MasterCard uses numbers between 51 and 55. One of the most important algorithms in bank card numbers is the Luhn Algorithm. This algorithm is a complex mathematical checksum validation formula used to determine the accuracy of identification numbers such as IMEI (International Mobile Equipment Identity) and – as this blog will demonstrate – bank cards numbers.

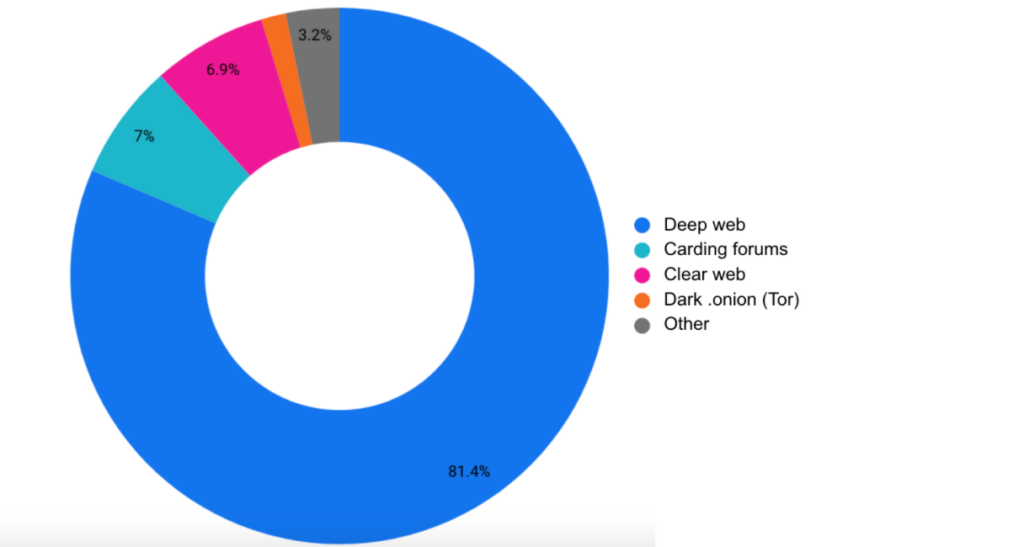

CybelAngel Study: credit card fraud detection

CybelAngel scans the expanse of the Internet, and among the data leaks detected we amassed a vast number of unprotected and valid BINs issued by small-sized to major banks. These BINs were processed through our proprietary processes including our advanced machine learning filters and analysis by our security experts. The output was a vast and valid stolen credit cards data set. (Note: The analysis is based on a year’s period of detections on CybelAngel’s regarding 12 big-to-medium sized banks. For statistical significance, we used 60 Bank Identification Numbers, which is publicly available information in order to establish a relatively approximate rate of exposure to malicious activity.) Our findings were worrisome enough to make any bank concerned for its assets. This CybelAngel study concluded there are an average of 2.000 credit cards per month freely accessible online. Most of these cards are traded free of charge and guaranteed to be operational. This means that each BIN number is subject to roughly 166 leaks. Cyber criminals are using communication channels such as, paste websites and carding forums on the clear, dark and deep web. Numeric evidence displays a high volume of credit card shares on the Dark web (on Tor), clear web, followed by carding forums and finally the paste and deep web platforms as the highest source of stolen credit cards.  Source: CybelAngel analysis 2019-2020 The low percent of card data on Tor websites can be explained by the fact that some of the biggest forums have been taken down and by the fact that it is a dynamic data source that is becoming more closely guarded with access highly restricted (e.g. more exclusive boards, providing identification documents, etc). NOTE: These statistics are being used for demonstration purposes regarding the volume and various sources of credit card data. The percent by source can be highly variable depending on the BIN keywords used and timing of exposure.

Source: CybelAngel analysis 2019-2020 The low percent of card data on Tor websites can be explained by the fact that some of the biggest forums have been taken down and by the fact that it is a dynamic data source that is becoming more closely guarded with access highly restricted (e.g. more exclusive boards, providing identification documents, etc). NOTE: These statistics are being used for demonstration purposes regarding the volume and various sources of credit card data. The percent by source can be highly variable depending on the BIN keywords used and timing of exposure.

Stemming Credit Card Fraud with CybelAngel

CybelAngel delivers the most exhaustive internet coverage on the market. We detect data leaks including credit cards before any fraudulent transactions can occur on the exposed accounts creating a major data breach. Our top priority is not only to reduce the risk but also preempt malicious activity before the damage is done.