Dark Web Guide 2026: The Biggest Threat Groups to Watch

Table of contents

The dark web feels closer to a digital wild west than ever. Alliances shift without warning. Crews clash for territory. Law enforcement knocks one gang down and another steps forward to fill the gap. It creates a space where no one stays dominant for long and where a small change in power can ripple across an entire underground economy.

This in-depth guide looks back at the major players who shaped the dark web through 2025 and considers what their activity means for the coming year. This shows security teams who they may face next and what kind of pressure their organisation could encounter as these groups evolve.

An introduction to the dark web

The dark web is a part of the internet that does not sit on the open web. It often operates via hidden services. You can only reach it through browsers that hide a user’s location and identity, such as onion sites. Crawlers such as Google or DuckDuckGo cannot access them, which is why threat actors rely on dedicated dark web search engines and curated directories.

Here’s a quick dark web glossary for beginners:

- Deep web: Any part of the internet that standard search engines cannot index. This includes private databases, login pages, medical records, and internal business tools.

- Surface web: The open part of the internet that search engines and web browsers can crawl, such as public websites and indexed pages.

- Tor network/ The Onion Router/ Onion links: An encrypted network that routes traffic through layers of relays to hide a user’s location. It is the primary way people reach darknet sites.

- Dark web search engines (e.g. Ahmia, Haystak): Search tools designed to find onion sites on the Tor network. Ahmia focuses on transparency and filtering illegal content, while Haystak offers advanced search options and paid access to deeper indexes.

There is a misconception that the dark web is inherently “bad”. But not everything there is illegal. For example, whistleblowers might contact journalists on the dark web to protect their identity. But unfortunately, this bends both ways, and criminal groups can also use it to run marketplaces, leak stolen data, and organise new scam campaigns, earning the dark web the reputation it has today.

What makes the dark web particularly challenging is its constant movement. Sites appear, disappear, or resurface under new names. Hackers migrate between forums depending on who they trust and which platforms survive law enforcement pressure. For anyone responsible for protecting a business, this shifting space can conceal early warning signs of attacks, leaked credentials, or emerging partnerships between threat actors.

State sponsored dark web players

State sponsored groups use the dark web as an extension of their wider operations. Some rely on it to trade exploits, monitor vulnerabilities, or test new malware behind layers of anonymity. Others stay quieter and use hidden forums to gather intelligence. This creates a space where national interests and criminal networks can blur, making it harder for security teams to track early signs of hostile activity.

1. Volt Typhoon

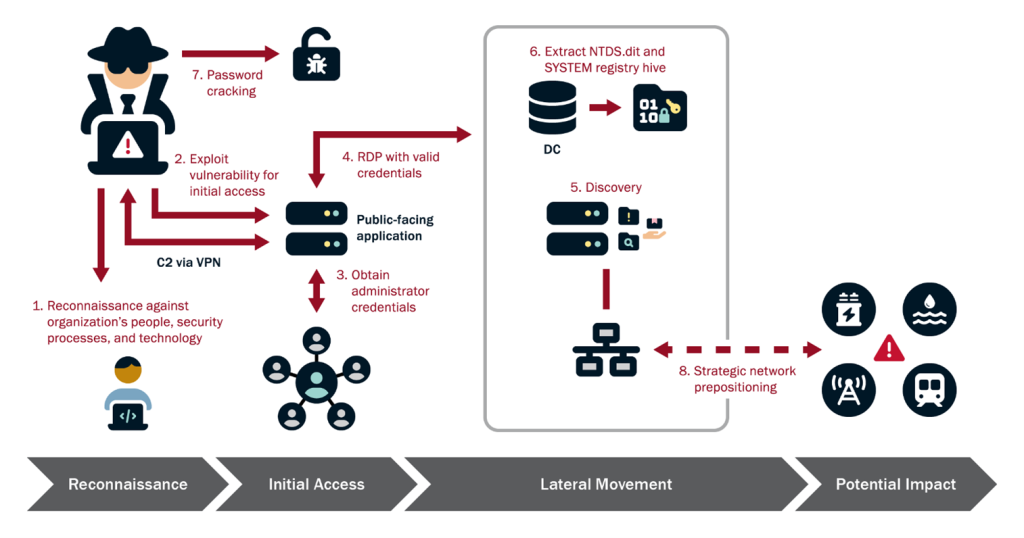

Volt Typhoon is a Chinese state linked cyber espionage group that has been active since 2021 and is known for blending into legitimate system activity through Living off the Land techniques. Their focus is long term access rather than noisy disruption, but the intent behind that access is to undermine US critical infrastructure and weaken military readiness in the Pacific.

They have targeted sectors such as communications, energy, and transportation, and their illegal activities have drawn warnings from agencies, including CISA. Analysts note that their choice of victims suggests preparation for potential operational disruption rather than routine intelligence collection.

2. Ruskinet

RuskiNet is a pro Russian hacktivist group first observed in early 2025 and is believed to operate from Eastern Europe while promoting Russian geopolitical interests. Their activity blends data leaks, phishing attempts, and disruptive campaigns that target critical infrastructure and government entities.

Analysts have not confirmed them as an advanced persistent threat (APT) group, yet their goals mirror the intent seen in groups like APT28 and APT29. RuskiNet has claimed attacks across the US, Canada, Israel, the UK, Turkey, and India, ranging from DDoS activity to questionable data leaks on dark web forums. Much of their output seeks to cause confusion and undermine public trust rather than deliver long term access.

3. NoName057(16)

NoName057(16) is a Russia aligned hacktivist collective known for large scale DDoS campaigns against NATO members and countries that support Ukraine. Active since 2022, they use botnets and other special tools to overwhelm financial institutions, government sites, and transport services, aiming to disrupt daily operations rather than gain long term access.

Their activity is high volume and politically driven, with a reported success rate of around 40%. Data from recent years shows a focus on Poland, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, Italy, and Spain as the group attempts to weaken support networks around Ukraine.

What’s next for state-sponsored groups in 2026?

Security teams should expect more activity that hides inside normal network traffic and depends on steady access rather than loud tactics. Volt Typhoon will likely continue to probe critical infrastructure through weak credentials and misconfigured devices, while Russia aligned groups such as RuskiNet and NoName05716 push disruption through DDoS pressure and selective leaks. These shifts will make intent harder to read, increasing the value of security measures such as real time dark web monitoring.

Coordinated dark web players

Threat groups that once competed for attention and victims are now forming alliances that strengthen their reach on the dark web. These partnerships can involve shared infrastructure, pooled negotiation channels, or coordinated leaks that mask who is driving an attack.

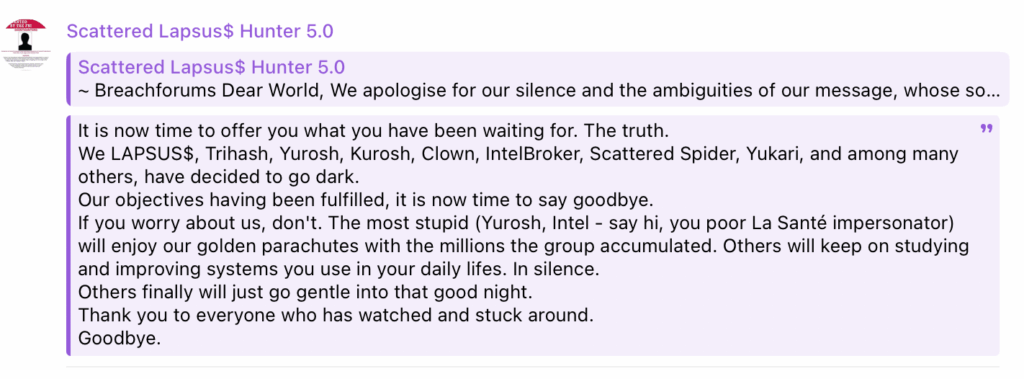

1. The Scattered LAPSUS$ alliance

The Scattered LAPSUS$ Hunters, sometimes called the Trinity of Chaos for their illicit activity, are an alliance formed from Scattered Spider, ShinyHunters, and LAPSUS$. Their strength comes from combining social engineering skill, access abuse, and personal data theft.

In the 2025 Salesforce breach, they used OAuth token compromise through a connected application to move through multiple environments and extract large volumes of customer and operational data. Once inside, they relied on Living off the Land techniques to blend with normal activity. The group hosts a TOR dark web leak site where they publish victim lists and samples of stolen records, reinforcing their role as a major ransomware driven actor.

2. The LockBit/ Qilin/ DragonForce alliance

In a similar case, LockBit, Qilin, and DragonForce have formed an unusual ransomware alliance that signals a shift toward more coordinated operations. Analysts observed shared infrastructure and leak site activity through 2025, indicating that the groups are aligning their strengths as each tries to regain or expand influence.

The alliance makes sense for these groups. LockBit is rebuilding after its takedown, Qilin is growing its extortion footprint, and DragonForce has moved from activism into commercial ransomware. Their cooperation blurs attribution and creates a more resilient ecosystem on dark web forums, making it harder for security teams to understand which actor is driving an attack or how many groups are involved.

What’s next for coordinated dark web players in 2026?

Alliances between groups will likely change shape as they look for new resources or safer ground. These partnerships can keep weak groups active and give stronger groups new entry points, which makes attribution less reliable. Good threat intelligence and dark web monitoring will matter even more in 2026, as security teams try to follow how these relationships form, break, or reorganise around major attacks.

Ransomware dark web players

Ransomware cybercriminals continue to shape much of the dark web economy, moving between forums, leak sites, and private channels as they search for new victims. This section looks at the groups that defined 2025 and how their activity may influence dark web cybercrime in the year ahead.

1. Scattered Spider

Scattered Spider is an adaptive cybercriminal group known for targeting large companies through detailed social engineering. Also called UNC3944, Oktapus, or Muddled Libra, they impersonate internal IT staff to obtain credentials, take over MFA processes, or install remote access tools. Once inside a network, they rely on Living off the Land methods and use tools such as AnyDesk or TeamViewer to move quietly while collecting data.

The group has recently escalated its activity by deploying DragonForce ransomware after exfiltrating sensitive information. Despite arrests, Scattered Spider resurfaced in late 2025 with messages hinting at wider, undisclosed breaches and a possible reorganisation under new identities.

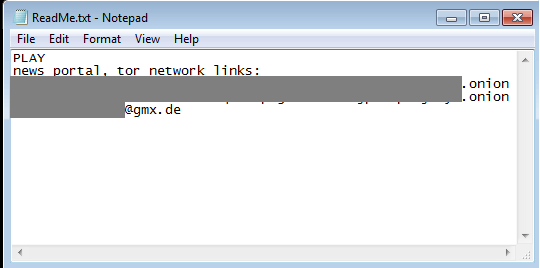

2. PLAY

PLAY ransomware, also known as Playcrypt, has been active since 2022 and is responsible for widespread attacks across North America, South America, Europe, and Australia. The group is known for high volumes of activity, with some months reaching more than 170 attempted attacks, and for operating as a closed organisation rather than relying on affiliates.

The group focuses on multi-extortion, stealing data before encrypting systems and directing victims to contact them through the dark web. Victims often reach these leak sites through Tor, sometimes routed through a VPN to avoid exposing their IP address. Ryuk’s intrusions often begin with exploitation of known vulnerabilities in Fortinet and Microsoft Exchange, followed by intermittent encryption and extensive use of LOLBins to stay hidden during lateral movement.

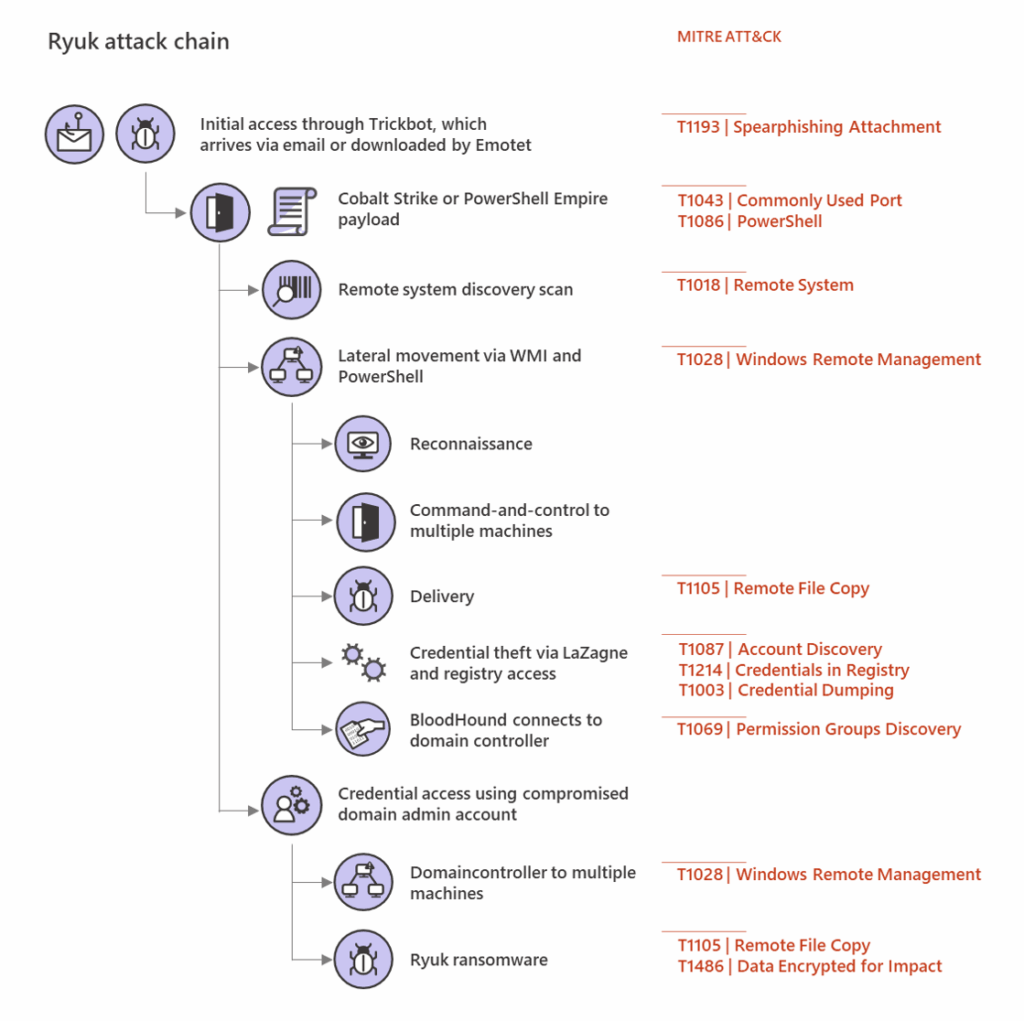

3. Ryuk

Ryuk is a long running ransomware operation known for precision targeting and severe operational impact. First seen in 2018, it focuses on large organisations and uses techniques that make recovery difficult, including the deletion of shadow copies and the rapid encryption of network drives.

Ryuk is linked to the Russian cybercriminal organisation Wizard Spider, with activity believed to run through a smaller cell known as Grim Spider. The group demands high ransoms and is routinely paid in cryptocurrency, often Bitcoin, to obscure transactions. Its focus on healthcare and other high pressure sectors keeps Ryuk active in 2025, despite years of scrutiny.

4. Cl0p

Cl0p, also known as Clop or TA505, is a long running ransomware group that first appeared in 2019 as a variant of CryptoMix and has since grown into a major extortion operation. Believed to be Russian speaking, the group uses a .clop extension for encrypted files and avoids systems located in CIS countries (Commonwealth of Independent States).

Now, the gang has moved far beyond simple encryption, adopting a quadruple extortion model supported by its Tor hosted leak site, CL0P^_-LEAKS. The group’s impact is significant, with more than $500 million in ransom payments linked to its activity and large scale campaigns such as GoAnywhere and MOVEit compromising hundreds of organisations. In February 2025 alone, it named 182 victims on its leak site.

What’s next for ransomware groups in 2026?

Closed ransomware groups will keep pushing for faster access and quicker exfiltration as they try to stay ahead of patch cycles and law enforcement pressure. Many are shifting toward quieter intrusion methods that rely on existing tools inside a network, which makes early detection harder. We can also expect more groups to disappear after leaks or arrests and then reappear under new names, keeping their operators active even when the brand fades.

Malware-as-a-service dark web players

Malware-as-a-service has lowered the barrier for criminal operations by giving affiliates ready made tools to run their own campaigns. Groups behind these services focus on development, infrastructure, and updates, while others handle intrusion and extortion. This model keeps their malware in constant circulation on the dark web and allows even small crews to cause significant disruption.

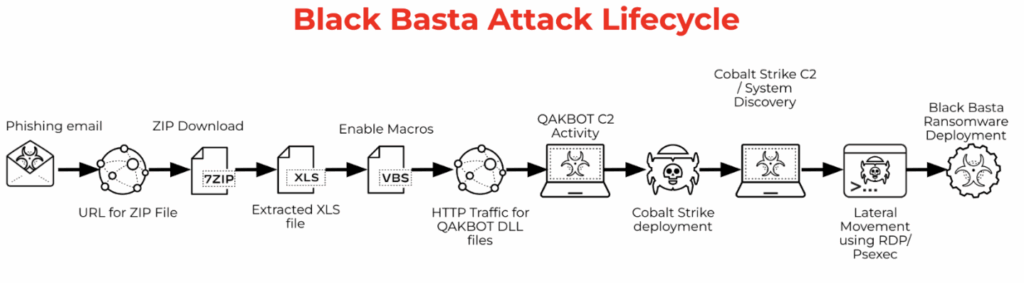

1. Black Basta

Black Basta emerged in 2022 with an unusually fast rise, listing more than 20 victims on its Tor based leak site, Basta News, within its first two weeks. Black Basta is known for a strict affiliate model, working only with a small circle of trusted partners rather than recruiting openly, which helps the group control operations and limit exposure.

The group has since hit more than 500 organisations across healthcare, manufacturing, construction, and other high value sectors. Their operations mix social engineering, custom tools for device compromise, and well known utilities such as PowerShell and Cobalt Strike. Although recent leaks exposed internal chat logs and forced the brand into silence, its operators have already reappeared under new ransomware names.

2. Lynx

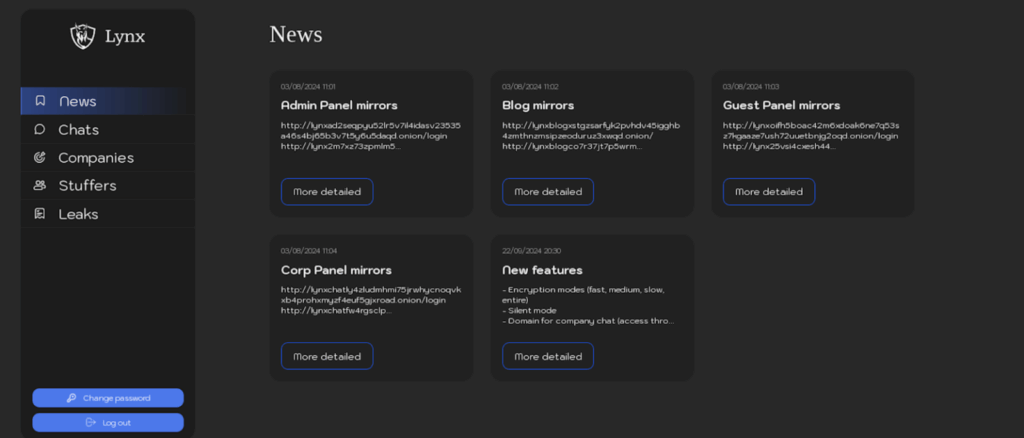

Lynx ransomware has been active since mid 2024 and operates as a structured malware-as-a-service programme aimed at small and medium sized businesses as well as larger enterprises. The group promotes an “ethical” targeting policy, avoiding government bodies, healthcare, and non profits, while still pursuing sectors such as finance, manufacturing, and architecture.

Lynx recruits affiliates through a detailed RaaS portal with sections for news, leaks, coordination, and tooling. Affiliates keep a large share of the ransom and control negotiations, and high performing partners can access extra services, including dedicated storage and a call centre used to pressure victims.

3. Akira

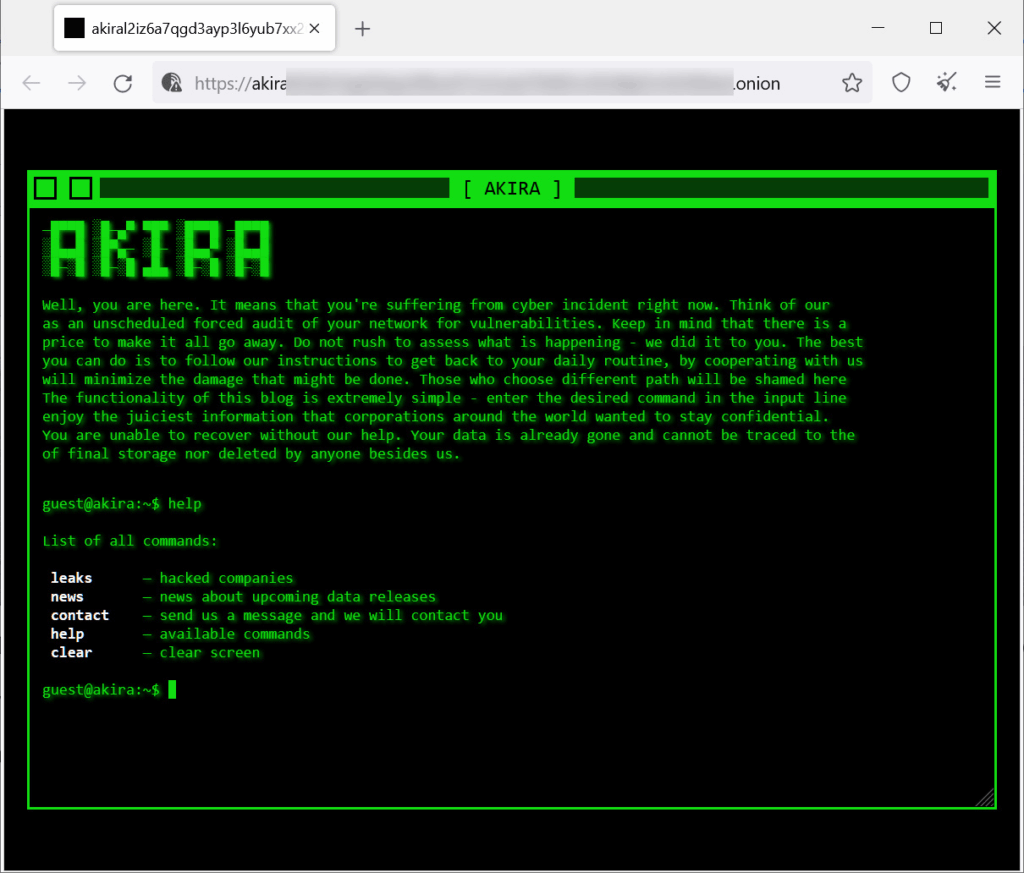

Akira is a ransomware-as-a-service group that appeared in March 2023 and has grown into one of the most active ransomware operators worldwide. Its malware is available to anyone who joins the programme, allowing affiliates to steal and encrypt data and demand ransoms that can reach several million dollars.

It maintains a distinctive dark web leak site styled like an old green screen console (see below), listing victims and publishing stolen data. The group focuses heavily on France and North America and has delivered rapid, high volume attacks, including exfiltration from Veeam servers in just a few hours. Analysts believe Akira’s origins trace back to the Conti organisation.

4. Lumma Stealer

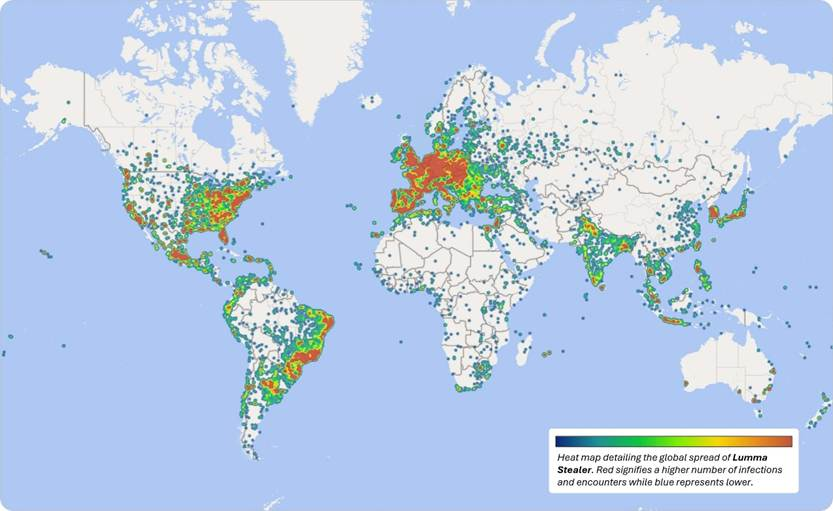

Lumma Stealer, also known as LummaC2, is an information stealing malware sold as a malware as a service package on Russian speaking forums. First seen in 2022, it offers cybercriminals a ready made way to harvest browser data, cryptocurrency wallets, and two factor authentication extensions before sending everything to C2 servers.

The malware is widely deployed, with close to 400,000 Windows machines compromised in early 2025. Even after a takedown effort by Europol and Microsoft, its operators quickly rebuilt their infrastructure. Lumma spreads through phishing emails, malvertising, fake repositories, and compromised sites that lure users into running malicious executables.

5. Pikabot

PikaBot is a malware loader that emerged in 2023 and has quickly become a preferred tool for threat actors after the fall of Qakbot. It delivers payloads through a modular design that supports injection, evasion, and its own C2 framework, allowing attackers to deploy spyware, keyloggers, or ransomware once access is gained.

The stealth malware uses strong anti analysis techniques and stops execution on systems set to Russian or Ukrainian to avoid attention in those regions. Researchers suspect Russian operators are behind it, and recent campaigns grew sharply after Qakbot’s dismantling, positioning PikaBot as the new loader of choice for many criminal groups.

What’s next for malware-as-a-service in 2026?

Malware-as-a-service will keep growing as developers release new loaders and stealers that are easy for others to use. These groups have shown they can recover quickly after takedowns, so their tools are likely to stay active across dark web forums and hidden services. Cybersecurity teams will need strong threat intelligence to understand how these malware families shift and how quickly they can appear in new campaigns.

How to stay ahead of dark web risks

The threat groups in this guide move quickly and often out of sight. Forums disappear, leak sites reappear under new names, and stolen data can spread long before a breach is confirmed. Without dedicated visibility, it is easy to miss early signs of trouble.

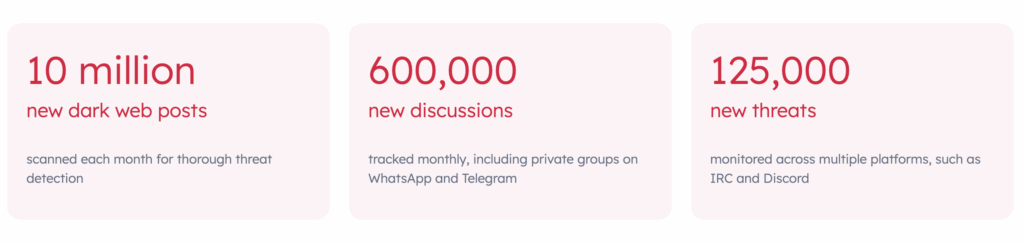

CybelAngel’s dark web monitoring gives teams a clear view of this activity. Our platform continuously scans hidden services, Telegram channels, and dark web forums to surface exposed data linked to your organisation. You receive timely, validated intelligence that helps you act before attackers gain momentum.

CybelAngel also offers on-demand investigations from experienced analysts who can confirm incidents and explain how a threat is unfolding. This support helps security teams respond with confidence in a space that rarely stays still.

Conclusion

The dark web will continue to change through 2026, with new groups emerging and familiar names returning under different identities. For security teams, following these shifts offers a clearer sense of what could reach them before an incident occurs. With strong threat intelligence and dark web monitoring in place, organisations can detect exposure early and respond with more confidence in an environment that moves quickly.