Why Microsoft SMBv1 Threats Linger [Tackle these Challenges]

Table of contents

SMBv1 and its variants can seem the same. But they unleash different challenges for all operating systems.

Did you know that despite Microsoft deprecating SMBv1 in a 2013 security update, it is still a favored (and available!) window for ransomware attacks?

In this blog we’ll explore why SMBv1 vulnerabilities continue to be exploited, and share how remote attackers are incentivized to exploit attacks via various SMB ports.

We’ll also review recent how you can carry out successful security updates to counter the targeting of SMB versions.

You’ll ultimately be guided about the continuous trail of related SMBv1 cybersecurity issues.

SMBv1 and malware: The story so far

Over late 2016 and early 2017, threat actors known as The Shadow Brokers, leaked offensive hacking tools obtained from the Equation Group, a group which multiple independent assessments link to the U.S. National Security Agency(NSA).

A few of these tools were subsequently integrated into various malware, with the pinnacle reached in May and June 2017, when the WannaCry ransomware and NotPetya/Nyetya wiper attacks infected or destroyed hundreds of thousands of computers worldwide. The attacks exploited a vulnerability in SMBv1 to spread their malware rapidly across networks with vulnerable hosts — both also used Mimikatz, a password-grabbing tool, to proliferate.

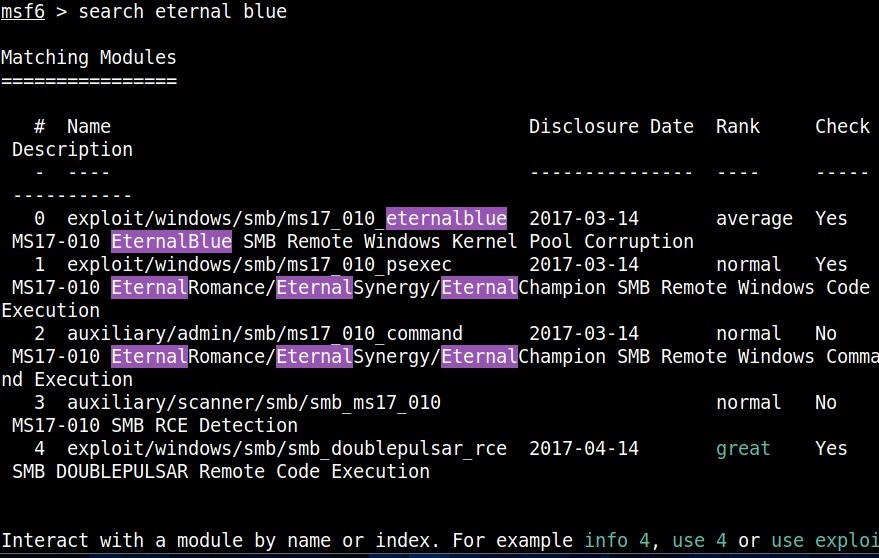

The adapted version of the EternalBlue exploit used in the attacks combined with a second NSA tool, DOUBLEPULSAR, to allow remote arbitrary code execution and deliver the WannaCry payload.

Despite Microsoft amping up its coordinated vulnerability disclosure process, the end result featured encrypted computers for hundreds of thousands of victims, companies, and governments, in nearly 150 countries.

Fast forward to the roaring twenties and albeit in slightly different ways, the same old SMBv1 server conversion is still cropping up.

A Rapid7 report found that in March 2020, between 500,000 and 1.3 million devices ran SMB services, with only around 343k devices using SMBv1 with authentication disabled (Shodan query). Of those, the vast majority ran Unix OSs, not Windows. In 2020, Avast reported blocking around 20 million EternalBlue exploit attempts every month.

This is a net improvement on Rapid7 and Shodan statistics from 2017, when between 2.3 and 5.5 million devices were running SMB services, and, when that number dropped to between 700,000 and 1.7 million. Not quite eradication, nor does it eliminate the risk of variants or new malware families using the same exploits. In 2022 attacks continued with a reported 91.88% attacks on port 445, which is the most common SMB port vulnerability.

Ransomware is not the only SMB threat

While CISA strongly recommends disabling SMBv1 internally on networks due to its vulnerabilities, ransomware gangs like WannaCry and NotPetya have waited in the wings to target those who have not.

But there are other threats that are also falling under the radar (including the exploitation of sensitive information).

Unauthenticated access to documents shared via the SMB protocol can be equally damaging to organizations. Back in 2017, 42% of servers with open SMB ports also allowed guest access to their data .

CybelAngel regularly detects and alerts its clients to SMB servers publicly hosting thousands of sensitive documents. In a previous report CybelAngel documented the detection of 70 billion files across nearly 500,000 unique servers in one month.

The servers we identify often belong to third-parties and suppliers.They often exist outside of the attack perimeter and control of the organization (and individual person using a Microsoft windows device).

Open SMB/CIF servers can contain:

- Confidential information regarding a company’s IT architecture

- Passwords

- Company logins for access to internal platforms and devices

- Other credentials for further authentications

How to protect against SMBv1 exploits

The US-CERT advises caution when considering disabling or blocking SMB, as it may impede access to shared resources like files and devices. They counsel that organizations should carefully evaluate the trade-offs between enhanced security and potential operational disruptions before implementing changes.

In general, patch this software regularly while making sure you can rollback any issues.

- Disable unauthenticated/guest/anonymous SMB access allowing us (and others) to find your sensitive documents.

- If you do not need SMB, don’t keep it open. Block ports 139 and 445 on your network perimeter.

- If you need it, prioritize upgrading to the SMBv2 or SMBv3 versions. It is standard on Windows 10, as SMBv1 is clearly no longer supported by Windows.

- Backup your data – securely, on a server with correctly configured authentication and solid encryption

- Invest in a heavyweight full coverage security solution that will scan your external perimeter for external attacks. Vendors who work in the EASM space are a critical asset in your defence against third party file sharing,

Wrapping up with Microsoft vulnerability resources

Overall it is clear that disabling SMBv1 and moving to newer, more secure versions of the protocol on Windows is recommended. Many of the ransomware attacks mentioned above can be mitigated. Patching systems, disabling SMBv1, and following security best practices avoid major damage.

Here are some classic smb 1.0 resources to help you manage patching and disabling SMB infrastructure:

- Microsoft SMBv1 Vulnerability Guide– CISA

- SMB Security Best Practices Guide-CISA

- How to detect, enable and disable SMBv1, SMBv2, and SMBv3 in Windows– Microsoft

You can also brush up on general cloud drive security best practices over on our blog.