Is WannaCry Still a Threat?

Table of contents

As the ransomware industry lives its golden age, the anniversary date of one of the widest ransomware attacks ever known slowly approaches. Four years ago and some 300,000 computer infections later, WannaCry ushered in the global era of cyber extortion. The remaining question is whether WannaCry has written its last words. It’s true that WannaCry is no longer trending. New (or recycled) malware strains, such as Maze, Netwalker, RagnarLocker or Ryuk (not to mention the recently fallen Emotet), appear far more active and threatening. In fact, a quick visit to Google Trends reveals that are few people even searching for WannaCry information. So, one might think it’s time to check it off the list of 2021’s cyber threats. Or should we? Run a SMB honeypot for 10 or 15 days and you’ll see WannaCry continues infecting systems and threatening people and organizations. And here is why.

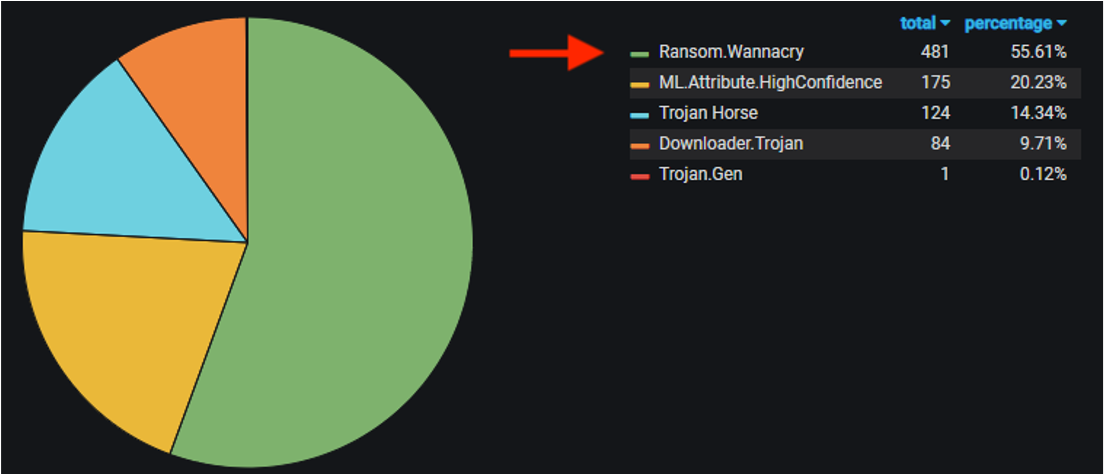

Top uploaded malware over last 30 days on this SMB honeypot. Wannacry infection attempts are #1.

The attack surface remains expansive

In a parallel universe far far away, everyone on the internet was learned about WannaCry and NotPetya in 2017. Shortly thereafter, every informed person and organization updated, patched, and protected all of their IT systems and network devices.

In the real world, this is what happened.

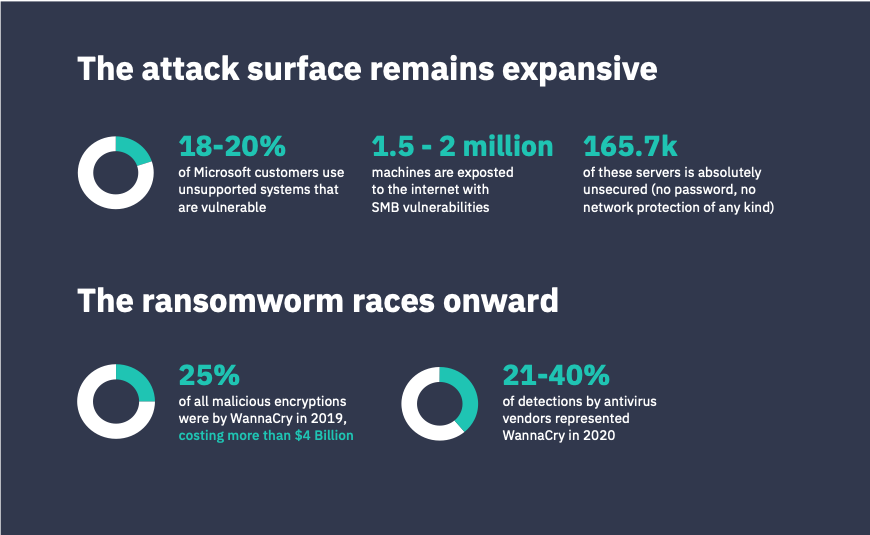

The WannaCry infiltration relies on the EternalBlue exploit kit, which directly leverages a flaw in the SMB protocol on Windows systems. While Microsoft corrected this flaw, millions of users did not patch their machines. The result is the unprotected SMB protocol still faces wormable vulnerabilities, namely CVE-2020-0796. As of March 2021, about 200 million computers run non-supported Microsoft OS, Windows 7 or older. Basically 18-20% of Microsoft customers use unsupported systems, many of which are connecting computers or local networks to the internet. The stark reality is between 1.5 and 2 million of machines are exposed to the internet with SMB vulnerabilities either through standard (445) or non-standard (139) ports. Over the last 12 months, 165.7k of these servers (~10%) have been identified by CybelAngel as absolutely unsecured (no password, no VLAN, no MAC address filtering, no network protection of any kind) while hosting files and content – which makes them both more vulnerable and more profitable targets. For the record, 92% of them were accessible on the non-standard port 139, meaning that their owner /administrator is likely not even aware of their existence.

The ransomworm races onward

Meanwhile, the intrinsic nature of WannaCry prevents it from slowing down. WannaCry is not just a ransomware, like Maze or RagnarLocker. It is a worm, that is self-replicating and self-propagating. This attribute means that WannaCry, once unleashed in the wild, never stops attempting to spread copies of itself. All it takes is just one vulnerable Windows system on a network, and the ransomware proceeds to spread throughout the entire network to infect any other unpatched machine, without any human intervention (such as opening an email or executing an .exe file). This why, despite the fact that WannaCry stopped making the headlines, the threat is still very real. Metrics speak loudest. In 2019 (two years after the initial burst), WannaCry was responsible for nearly 25% of all malicious encryptions – making it the most common hack of the year and costing more than $4B. The next most popular malware, GrandCrab, was responsible for “only” 12% of encryptions. In 2020, antivirus vendors announced that WannaCry represented between 21% (Kaspersky) and 40% (ESET) of their respective detections. In addition, some ISPs continue to block the killswitch domains, making their countries disproportionately affected to the spread.  Will it ever end? Unfortunately, efficient malware is virtually immortal. They may hibernate, but rarely do they truly die. Remember Conficker (2008-worm) or even MyDoom (2004-trojan)?

Will it ever end? Unfortunately, efficient malware is virtually immortal. They may hibernate, but rarely do they truly die. Remember Conficker (2008-worm) or even MyDoom (2004-trojan)?

Both are still alive and still in the wild. Furthermore, over the last few years we’ve seen how cyberthreat ecosystems are able to “improvise-adapt-overcome” by re-using older malware strains (e.g. ZeuS or Emotet) that evolve from simple trojans to a complete malware-as-a-service industry. If such a thing has not already happen to WannaCry yet, no one can predict whether or when it may occur. Nothing is, however, so bad that there is not some good in it. In many ways, WannaCry’s striking power has reframed the cybersecurity business landscape for the better. Organizations are better educated and prepared to prevent and protect themselves from ransomware threats. The CISO role and associated budget has been elevated. Executive management and boards are cognizant of the need to address and manage enterprise digital risk. Resources are being allocated to identify and resolve vulnerabilities, as well as to monitor and protect sensitive data from falling victim to a ransomware attack. Learn more about how to protect against ransomware attacks in our